Rectal Prolapse

Abstract

Rectal prolapse is a condition in which the rectum (the last part of the large intestine before it exits the anus) loses its normal attachments inside the body, allowing it to telescope out through the anus, thereby turning it “inside out”. While this may be uncomfortable, it rarely results in an emergent medical problem. However, it can be quite embarrassing and often has a significant negative impact on patient’s quality of life.

Key words

Rectal prolapsed, pathophysiology, investigation, diagnosis, general management & constitutional homoeopathic treatment.

Introduction

The term rectum refers to the lowest 12-15 centimeters of the large intestine. The rectum is located just above the anal canal. Normally, the rectum is securely attached to the pelvis with the help of ligaments and muscles. This attachment firmly holds the rectum in place. Various factors, such as age, long-term constipation and the stress of childbirth may cause these ligaments and muscles to weaken which means that the rectum's attachment to the body also weakens. This causes the rectum to prolapse. Occasionally, large hemorrhoids may predispose the rectum to prolapse. Rectal prolapse is an uncommon disease and primarily affects elderly people. The disease is rare among children. Affected children are usually younger than 3 years. Men develop rectal prolapse much less frequently than women do. In the United States, rectal prolapse is extremely rare.

Classification

The different kinds of rectal prolapse are:

• Full thickness (complete), where all the layers of the rectal wall prolapse or involve the mucosal layer only (partial)

• External if they protrude from the anus and are visible externally

• Internal rectal intussusception (occult rectal prolapse, internal procidentia) can be defined as a funnel shaped infolding of the upper rectal (or lower sigmoid) wall that can occur during defecation. Another definition is "where the rectum prolapses but does not exit the anus".

• Circumferential, where the whole circumference of the rectal wall prolapse

• Segmental if only parts of the circumference of the rectal wall prolapse

Rectal prolapse and internal rectal intussusception has been classified according to the size of the prolapsed section of rectum, a function of rectal mobility from the sacrum and infolding of the rectum. This

classification also takes into account sphincter relaxation.

• Grade I: nonrelaxation of the sphincter mechanism

• Grade II: mild intussusception

• Grade III: moderate intussusception

• Grade IV: severe intussusception

• Grade V: rectal prolapsed

Aetiology

The exact cause of this weakening is unknown; however, rectal prolapse is usually associated with the following conditions:

• Advanced age

• Chronic constipation

• Chronic diarrhea

• Long-term straining during defecation

• Pregnancy and the stresses of childbirth

• Previous surgery

• Cystic fibrosis

• Whooping cough

• Multiple sclerosis

• Paralysis (Paraplegia)

• Weakened pelvic floor muscles, Weakened anal sphincter muscles

• Genetic susceptibility, since it appears that some people with rectal prolapse have a blood relative with the same condition

• Parasitic infection, such as schistosomiasis.

• Any condition that chronically increases pressure within the abdomen, such as benign prostatic hypertrophy or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

• Structural problems with the ligaments that tether the rectum to its surrounds

• Congenital problems of the bowel, such as Hirschsprung’s disease or neuronal intestinal dysplasia

• Prior trauma to the lower back

• Disc disease in the lower back

Symptoms

The symptoms of a prolapsed rectum are similar to those of hemorrhoids; however, rectal prolapse originates higher in the body than hemorrhoids do. Early in the development of a prolapsed rectum, the protrusion may occur during bowel movements and retract afterwards. The protrusion may become more frequent and appear when the person sneezes or coughs. Eventually, the protruding rectum may need to be manually replaced or may continually protrude. People with internal intussusception, in which the rectum is displaced but does not protrude from the body, often experience difficulty with bowel movements and a sense of incomplete bowel movements. A person with a prolapsed rectum may feel tissue protruding from the anus and experience the following symptoms:

• Pain during bowel movements

• Mucus or blood discharge from the protruding tissue

• Fecal incontinence (inability to control bowel movements)

• Loss of urge to defecate (mostly with larger prolapses)

• Awareness of something protruding upon wiping

Complications

1. Risk of damage to the rectum, such as ulceration and bleeding

2. Incarceration – the rectum can’t be manually pushed back inside the body

3. Strangulation of the rectum – the blood supply is reduced

4. Death and decay (gangrene) of the strangulated section of the rectum.

Diagnosis/ Investigation

History

History of constipation is important because some of the operations may worsen constipation. Fecal incontinence may also influence the choice of management.

Physical examination

Rectal prolapse is diagnosed by examination. In cases where the rectum goes back inside by itself after passing a bowel motion, the person may have to bear down during examination by the doctor to show the prolapse in order to confirm the diagnosis.

Rectal prolapse may be confused easily with prolapsing hemorrhoids. Mucosal prolapse also differs from prolapsing (3rd or 4th degree) hemorrhoids, where there is a segmental prolapse of the hemorrhoidal tissues at the 3,7 and 11’O clock positions. Mucosal prolapse can be differentiated from a full thickness external rectal prolapse (a complete rectal prolapse) by the orientation of the folds (furrows) in the prolapsed section. In full thickness rectal prolapse, these folds run circumferential. In mucosal prolapse, these folds are radially. The folds in mucosal prolapse are usually associated with internal hemorrhoids. Furthermore, in rectal prolapse, there is a sulcus present between the prolapsed bowel and the anal verge, whereas in hemorrhoidal disease there is no sulcus. Prolapsed, incarcerated hemorrhoids are extremely painful, whereas as long as a rectal prolapse is not strangulated, it gives little pain and is easy to reduce.

The prolapse may be obvious, or it may require straining and squatting to produce it. The anus is usually patulous, (loose, open) and has reduced resting and squeeze pressures. Sometimes it is necessary to observe the patient while they strain on a toilet to see the prolapse happen (the perineum can be seen with a mirror or by placing an endoscope in the bowl of the toilet). In cases of suspected internal prolapse, diagnostic tests may include - Proctoscopy/ sigmoidoscopy/ colonoscopy, Videodefecography, Colonic transit studies and measurement of the anorectal muscle activity (anorectal manometry), Anal electromyography/Pudendal nerve testing. If the person has experienced rectal bleeding, the doctor may want to do a number of tests to check for other conditions such as bowel cancer.

About 11 per cent of children with rectal prolapse have cystic fibrosis, so it is important to test young people for this condition too.

Management

Treatment depends on many individual factors, such as the age of the person, the severity of the prolapsed and whether or not other pelvic abnormalities are present (such as prolapsed bladder). Treatment options can include:

• Diet and lifestyle changes to treat chronic constipation – for example, more fruit, vegetables and wholegrain foods, increased fluid intake and regular exercise. This option is often all that’s needed to successfully treat rectal prolapse in young children

• Change to toileting habits – such as not straining when trying to pass a bowel motion. This may require using fibre supplements or laxatives

• Securing the structures in place with surgical rubber bands – in cases of mucosal prolapse

• Surgery

Complications of surgery for rectal prolapse

Possible complications of surgery include: • Allergic reaction to the anaesthetic • Haemorrhage • Infection • Injury to nearby nerves or blood vessels • Damage to other pelvic organs, such as the bladder or rectum • Death (necrosis) of the rectal wall • Recurrence of the rectal prolapse.

Homoeopathic Treatment

Homoeopathic Treatment based on symptoms similarity (Totality of symptoms). For selection of remedy, a detailed case taking is necessary. Apart from this, the repertory is very useful.

Case Report

Preliminaries

• Name – Mr. Jagdish Prasad

• Age – 72 Years

• Sex/Religion – Male/ Hindu

• Marital Status – Married

• Diet – Vegetarian

• Address – 286, Muktanand Nagar, Jaipur, Rajasthan. Pin – 302018

Present Complaints

A 72 years old hindu male with known case of rectal prolapse has bleeding anus. Bleeding clotted, painless. Flatulence in abdomen > by eating, frequent stools 4-5 times daily, pain in right ankle, throbbing pain > massage, pain < standing from sitting. Vertigo < standing, sitting < motion, changing position > lying. Constipation- stool has to be removed mechanically. Unsatisfactory stool.

Past History

Nothing Significant

Family History

Father died- Natural death. Mother died – H/O Hypertension

Physical Generals

Appetite – Good

Desire – Juice

Thirst – 8 – 9 glasses of water daily

Tongue – Moist, purplish in color

Stool - Constipation- stool has to be removed mechanically

Urine – Frequent, cannot hold

Sweat – Nothing Significant

Thermal- Chilly patient

Mental General

Memory weak, Desire to be alone

Clinical Examination

Built- Tall, Thin person

Pulse – 68/minute; B.P. – 160/90 mm of Hg

Systemic Examination – CVS, CNS, Respiratory system –No abnormalities detected

Totality of Symptoms

Rectum prolapsed stool during.

Bleeding from anus, painless.

Flatulence in abdomen > by eating.

Pain in right ankle, throbbing pain, < standing from sitting, > massage.

Vertigo < standing, sitting, < motion, changing position > lying.

Urine frequent, cannot hold.

Constipation- stool has to be removed mechanically. Unsatisfactory stool, frequent stools 4-5 times daily.

Chilly patient.

Built – Tall, Thin person.

Memory weak, Desire to be alone.

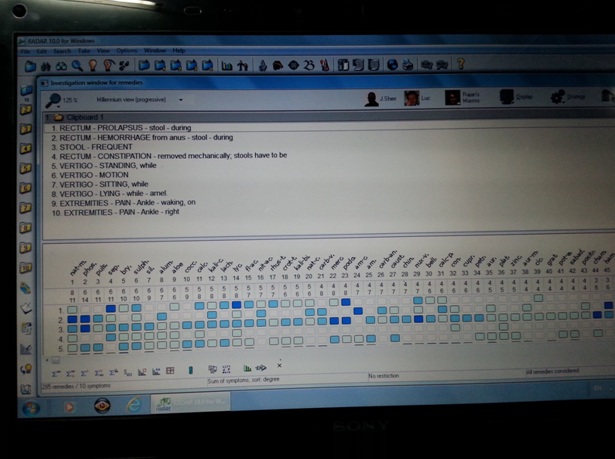

Repertorisation done by RADAR 9.1 using synthesis repertory

After analysis & Evaluation of symptoms, Repertorisation and consultation of MATERIA MEDICA Medicine selected was Phosphorus.

Medicine prescribed

Phosphorus 200/ 1 dose State, followed by placebo/ TDS for 15 days. Patient felt better in constipation, prolapsed. Bleeding stops completely. Again placebo repeated for 30 days. No complaints at all.

Conclusion

Rectal prolapse may occur without any symptoms, but depending upon the nature of the prolapse there may be mucous discharge (mucus coming from the anus), rectal bleeding, fecal incontinence.

Rectal prolapse is generally more common in elderly women, although it may occur at any age and in both sexes. It is very rarely life-threatening, but the symptoms can be debilitating if left untreated. Most external prolapse cases can be treated successfully. For this, we should consider the constitution, mental generals for the selection of most appropriate homeopathic remedy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (References)

1. ASCRS website, 2008 Core Subjects; Varma, M. G. “Prolapse, Intussusception, and SRUS”

2. Varma, M., Rafferty, J., Buie, W. D.; Standards Practice Task Force, American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice Parameters for the Management of Rectal Prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(11):1339-1346.

3. Gourgiotis S, Baratsis S. Rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007 Mar. 22(3):231-43. [Medline].

4. Harmston C, Jones OM, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. The relationship between internal rectal prolapse and internal anal sphincter function. Colorectal Dis. 2011 Jul. 13(7):791-5. [Medline].

5. Kairaluoma MV, Kellokumpu IH. Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand J Surg. 2005. 94(3):207-10. [Medline].

6. Altomare DF, Binda G, Ganio E, De Nardi P, Giamundo P, Pescatori M. Long-term outcome of Altemeier's procedure for rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Apr. 52(4):698-703. [Medline].

7. Marderstein EL, Delaney CP. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Oct. 4(10):552-61.

8. Randall J, Smyth E, McCarthy K, Dixon AR. Outcome of laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for external rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2014 Nov. 16(11):914-9 .

9. Hetzer FH, Roushan AH, Wolf K, Beutner U, Borovicka J, Lange J, et al. Functional outcome after perineal stapled prolapse resection for external rectal prolapse. BMC Surg. 2010 Mar 8. 10:9.

10. Tschuor C, Limani P, Nocito A, Dindo D, Clavien PA, Hahnloser D. Perineal stapled prolapse resection for external rectal prolapse: is it worthwhile in the long-term?. Tech Coloproctol. 2013 Apr 24.

11. Altomare, Donato F.; Pucciani, Filippo (2007). Rectal Prolapse: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Springer. p. 12.

12. Kim, Donald G. "ASCRS core subjects: Prolapse and Intussusception". ASCRS. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

13. Kiran, Ravi Pokala. "How stapled resection can treat rectal prolapse". Contemporary surgery online. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

14. Madhulika, G; Varma, MD. "Prolapse, Intussusception, & SRUS". ASCRS. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

15. www.DrThindHomeopathy.com

16. Homoeopathic Materia Medica by William BOERICKE, reprint edition 2000. B. Jain publisher PVT Ltd.

17. wikipedia.org/wiki/prolapsed rectum.

18. www.similibis.com

19. Schroyens, Frederik Synthesis repertory Version-9.1 Repertorium Homeopathicum Syntheticum B. Jain publisher PVT Ltd.